October 2023

By Richard Fleming

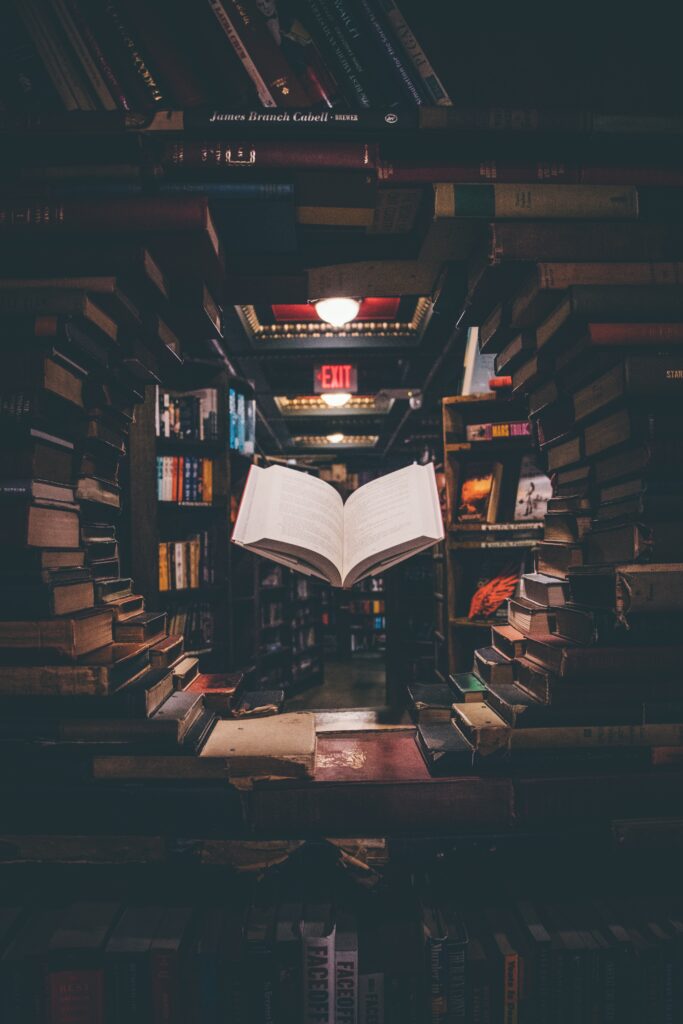

Photo courtesy of Amilrali Mirhashemian

(Baby Boomers are far from homogeneous. We face differing financial, health, social, and family situations. My ideas in this post will not apply to every Boomer, but I think they may apply to many.)

In the early 1980s a novel term for Baby Boomers began to garner attention. We became known as the “Sandwich Generation.” This concept achieved wide currency, even though it emerged before social media claimed its role as the sole arbiter of what ideas should be popular. The moniker was based on the fact Boomers carried significant responsibility for the welfare of both the generation above us (our aging parents) and the generation below (our children). We found ourselves in the middle of a proverbial sandwich.

This idea was accepted by many Boomers. Being called the Sandwich Generation was not a pejorative, but an honorable acknowledgment of our role in society. We were the key ingredient binding together the three generations. I cannot speak to how the top and bottom layers of the sandwich viewed this metaphor, but at the time I don’t recall much grumbling from either our parents or our kids.

My wife and I indeed spent much time and energy making sure our parents lived safely and securely through the ends of their lives. And we did our best to make sure our children were well-positioned to be independent, responsible, ethical young people. We served these roles reasonably well, though in retrospect we certainly could have done some things differently. But we provided the best support we could.

* * *

Today, Boomers can no longer be called the Sandwich Generation. For most of us, our parents have passed on, so we are no longer responsible for their well-being. And our children are mostly – with a few significant caveats – off on their own. At least they don’t require, and certainly do not want, parental guidance or advice.

So have we bequeathed the Sandwich Generation role to Gen X and Millennials? Not exactly. Today’s reality is more complex. To begin with, many Boomers are still reasonably self-sufficient. Yes, we have accumulating health problems and other challenges, but most of us can still manage our lives without supervision or support from our children. Most of us have not yet assumed our role as the top slice of bread.

Another way the sandwich concept falters is that many of the children of the Boomer generation still need help from their parents. This is not a critique of younger folks. It is rather a reflection of the difficulties our society and economy have created for younger generations. These problems often require us to support our children in a number of ways.

High-quality childcare is hard to find and tends to be expensive, so many of us spend significant time babysitting grandchildren. Some evidence suggests that Boomers spend more time babysitting grandchildren than did previous generations. This is partly because, compared to our parents’ generation, we tend to live longer and are in generally better health. Simply put, we have more time and energy available for babysitting than our forebears. We take on this responsibility willingly and are rewarded with love beyond measure.

Boomers often continue to provide their children financial support. Again, this is not a criticism. Today’s economic reality tends to make it harder for young people to generate enough income to pay for food, housing, and all the other expenses of daily living. Real incomes have dropped for many jobs compared to the mid-20th Century. And costs of living are higher. It is true that many Boomers also live with financial insecurity. But many others are in a position to help their children financially.

Nowadays, Boomers also open our homes to our kids more often than was the case in the past. For a variety of reasons, our children often find themselves in the position of needing to move back home for periods of time.

All these situations represent a major change from when we were in the workforce. When we Boomers were in our prime working years, we tended to be financially better off than our parents had been when they were working. And we also tended to be better off in that stage of life than our kids are today in their prime working years.

* * *

Where does this leave things with the Sandwich Generation concept? My proposal is to start identifying Boomers as the Open-Faced Sandwich Generation. We no longer have responsibility for the top slices of bread. But we still have a fair amount of responsibility for the lower slices. I feel this open-faced sandwich metaphor accurately describes many, though not all, Boomers.

But it is a transitory image. We Boomers are growing older each year. I have little doubt we will all soon become top slices of bread. My personal challenge, when that time comes, will be deciding whether to see myself as pumpernickel or sourdough.

* * *

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to be notified of future posts. Subscriptions are free.